Fine of the Month: December 2011

(Evyatar Marienberg and David Carpenter)

1. The Stealing of the “Apple of Eve” from the 13th century Synagogue of Winchester

This month we welcome a contribution from Evyatar Marienberg (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), with an introduction by David Carpenter (KCL), discussing the nature of the mysterious “apple of eve” apparently stolen from the Winchester synagogue.

1.1. Introduction by David Carpenter

⁋1In January 1252, King Henry III sent a remarkable writ to the sheriff of Hampshire. It was copied onto the fine rolls and in translation runs as follows:

Concerning taking an inquisition. Order to the sheriff of Hampshire to inquire by the oath of twelve of the more law-worthy Jews of Winchester by their roll whether Cressus of Stamford, Jew, violently seized and took away the apple of Eve from the synagogue of the Jews in the same city to the shame and opprobrium of the Jewish community. If, by that inquisition, he shall be found guilty of that deed, then they are to distrain Cressus immediately by his rents, houses and chattels to give one mark of gold to the king for that trespass. Witnessed as above. By the king. 1

⁋2Perhaps the chief interest of the writ lies in the identity of the ‘apple of Eve’, which Cressus of Stamford was accused of stealing to the shame and opprobrium of the Winchester Jews. Before addressing that question, a brief word putting the writ into context may be helpful.

⁋3The writ is said to be ‘witnessed as above’. This refers to an entry next but one above in fine rolls where another writ is enrolled, a writ which ends with the statement that it was witnessed by the king on 19 January 1252 at Geddington. 2 This then was also the place and date of issue of our writ. Geddington itself is in Northamptonshire and was a favourite hunting lodge of twelfth and thirteenth-century kings. Later, of course, it was graced, indeed still is graced, by an Eleanor Cross. Henry III himself was no great huntsman, and he often saw Geddington only in the course of travels to and from the north. 3 On this occasion, he was on his way south, having attended the marriage at York of his daughter Margaret to King Alexander of Scotland.

⁋4The writ is said to be ‘by the king’, ‘per regem’, which means that the king has authorised the chancery to draw it up. In some periods, where the great majority of writs are either unauthorised, or where authorised, are authorised mostly by ministers, such a note might be interpreted as indicating a particularly personal initiative of the king. Around this time, however, a very high proportion of writs in all the chancery rolls are said to ‘by the king’. Perhaps Henry III was working much harder and taking a closer interest in business than before. Alternatively, it may just be that the chancery had altered its procedures, and had decided to record as ‘by the king’, writs which were authorised in the routine business sessions over which he presided, writs it had previously left without an authorisation note. Whatever the truth here, it seems highly likely that Henry was personally involved in issuing the writ about ‘the apple of Eve’. Winchester was both his birth place and a favourite residence. He was deeply concerned with what happened there, as he was with the Jewish affairs in general. His efforts to convert the Jews to Christianity and the appalling punishments he inflicted on the Lincoln Jews after accusations of ritual murder have already formed the subject of one ‘Fine of the Month’. 4

⁋5Just how the incident came to the notice of the king we do not know. Given there are around 120 miles between Winchester and Northampton, it must have occurred at the very least several days before 19 January. It may, of course, have taken place much earlier still and only now have come to the king’s attention. It is worth noting that Henry had not been in Winchester since July 1251. The writ does not say who brought the affair to the king’s notice, but perhaps the likely candidates are the Jews of Winchester themselves. It was they, after all, who had suffered the ‘shame and opprobrium’. If, moreover, Cressus was convicted of the theft, there was presumably the chance of recovering the ‘apple of Eve’. Henry III was, as we have said, an oppressor of the Jews, but he could also act as their protector, and wish to treat them fairly. In August 1251, he intervened after the Jew, Samar’ of Winchester, complained to him about the undue demands of the justices of the Jews. 5 Often, of course, such interventions had to be paid for. There is no evidence that the Jews of Winchester paid for their writ, if it was their writ, but it is always possible that they gave something cash down direct into the wardrobe in which case there might be nothing on the fine rolls and there would be no evidence for the payment. On the other hand, it is possible the king issued the writ without charge from concern over the alleged trespass, and the hope of profiting from it. If convicted, Cressus was to pay him one mark of gold. This was at a time when Henry III was saving a treasure in gold for his crusade and was asking for a wide variety of payments be made in that metal. One mark of gold was the weight in gold of a mark of silver. At a conversion ratio of ten to one, it was thus worth ten marks or £6 13s 4d of silver. 6 Given that around this time an income of £15 a year rendered one liable to take up knighthood, this was not an inconsiderable sum. Cressus was evidently a Jew of some means, as one can deduce also from the reference to his rents, houses and chattels. Since it was apparently the Jews of Winchester who were to distrain him to pay the mark of gold, his property was presumably in the city.

⁋6Unfortunately, there appears to be no evidence as to the results of the inquiry mounted by the twelve law-worthy Jews of Winchester. Indeed, working through the indexes of the obvious printed sources, I have found no more about either the incident or Cressus of Stamford. Where light can perhaps be shed is on the nature of the ‘apple of Eve’ which he had perhaps taken from the synagogue.

1.2. ‘The Apple of Eve’ by Evyatar Marienberg

⁋1 What exactly was the object that Cressus of Stamford 7 was accused of violently seizing? How come that the “Apple of Eve”, whatever this object was, had been in the synagogue of Winchester? Why would Cressus want it, and why was the community so upset by this act that it was reported to the king’s agents?

⁋2Some suggested this “fruit” was actually a type of ornament: a finial, often spherical, and generally made of silver or gold, which traditionally protects the wooden staves of the Torah scroll. This suggestion—although interesting in that it explains the presumed theft as motivated by financial reasons, thus providing a fair answer to the questions of why the object was in the synagogue and why the community was so bothered by its theft—has several problems. The first is that although in some communities the term “apple” (in Hebrew: Tapu’ah. Plural: Tapuhim) is used to refer to such a finial, this seems to be the practice only in Spanish and Sephardic communities. In all other communities, the common name is “pomegranate” (Rimon. Plural: Rimonim). One would imagine that communities in England would use also the term “pomegranate”. Moreover, even though finials are mentioned in Jewish sources already by the twelfth century (and thus prior to our case), these early mentions are from North Africa. One might wonder whether the practice of having such finials had reached England by the thirteenth century. 8 One can also wonder why a person who was not, as suggested earlier, a pauper, would put his reputation at risk by stealing a liturgical object, even one of some monetary value. The last problem is perhaps the most substantial: the theory that the suspected theft was of a finial does not explain why the text in the Rolls speaks explicitly about “Eve’s Apple” (in the Latin text: pomum eve).

-

- Decorative finials of a Torah scroll

⁋3I believe the answer is elsewhere, and that it is in fact related to the Jewish festival of Sukkot. This autumn festival revolves around two particular ritual practices: The first obligation is to spend parts of each of the seven days of the festival, especially during meals, in a specially built “Sukkah” (booth), which is actually a type of hut, made according to precise rules. This custom is based on Leviticus 23:42-43:

You shall dwell in booths for seven days. All who are native Israelites shall dwell in booths, that your generations may know that I made the children of Israel dwell in booths when I brought them out of the land of Egypt.

⁋4The second obligation calls for the assembling of four specific types of plants (“The Four Species”), holding them together every morning, and saying a special blessing over them. This practice is based on Leviticus 23:40:

And you shall take for yourselves on the first day the fruit of beautiful trees, branches of palm trees, the boughs of leafy trees, and willows of the brook; and you shall rejoice before the LORD your God for seven days. 9

⁋5Of course, like all Jewish practices based on the Bible, the current shape of this last ritual depends on hundreds of years of rabbinic interpretation. One of the many adjustments made by the rabbis regarding this last practice has been to extend it, although under a different category, to apply not only to the first day of the festival, but to all seven. Moreover, in the classic rabbinic literature, the rather vague biblical description of the various plants in the verse we quoted was explained as referring to very specific “species”. Thus, the “leafy tree” was defined as myrtle (Myrtus communis), and the “fruit of beautiful trees” was identified as a citron (Citrus medica), or, in Hebrew, Etrog. 10 A citron is a relatively dry yet fragrant citrus fruit. Citrons can take rather different shapes, but they generally look like a big lemon. The origin of the citron is probably in Southeast Asia, and some scholars believe the citron, one of the most ancient members of the citrus family, was the first citrus fruit that reached the Mediterranean basin, with others members of this botanical group arriving probably close to a millennium later, during the Arab conquests. When exactly the citron arrived in Palestine is difficult to tell. Although the citron most certainly did not exist in the Middle East during the time when the Pentateuch was written (thus making it unlikely that the biblical author(s) originally intended for it to be used in the ritual), it seems this Jewish identification is older than its first appearance in rabbinic sources of the early third century CE. 11 The citron/Etrog seems to appear on Jewish coins from the years 69–70 CE, 12 and seems to be described by Josephus Flavius in his work Antiquities of the Jews, written in the last decade of the first century CE. Some scholars suggest that the identification happened a few centuries earlier, at some point during the late Second Temple period; others are more sceptical and believe that the actual ritualistic use of the citron, and its naming as Etrog, happened more recently. 13 Regardless of this debate, for our purposes, this historic question is of little relevance: By the Middle Ages, this identification seems already solid and stable. 14

-

- A Sukkah and the Four Species, Austria, October 2011

⁋6Today, practicing Jews all over the world can obtain an Etrog without much difficulty if they wish to accomplish the commandment of the “Four Species”. Often, the Etrogim are grown in, and sent from, Israel. 15 But in the past, obtaining an Etrog was not as easy. Judging, though, from the available primary sources and the extremely high number of texts discussing the accomplishment of this commandment, it seems Jewish communities in medieval Northern Europe were also able to obtain (with what frequency we do not know) Etrogim from warmer places. 16 Luckily for the Jews, they were not the only group interested in citrons. Although citrons were probably not grown in masses, they were desired for their claimed medicinal attributes, smell, and maybe also for their unique taste. Therefore, a market for citrons, although perhaps small, existed in Europe. 17

-

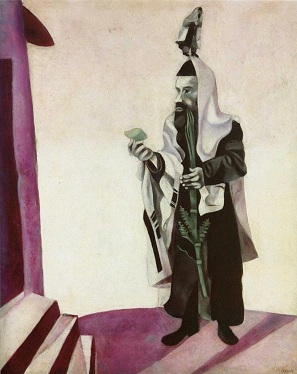

- Marc Chagall, Feast Day (A Rabbi with Etrog), 1914

⁋7Having said that, it is still rather clear that getting them was no easy feat, and that it required the involvement of merchants, commercial networks, and probably significant sums of money. 18 If today most practicing adult male Jews would be likely to acquire their own Etrog every year, 19 and many would acquire additional ones for male children, it is likely that in the past, entire communities had to rely on a very small number of Etrogim, or maybe even a single one. The problem was not only obtaining a specimen, but getting a kosher one. In order to be perfectly valid for its liturgical use, the fruit must be without blemish, not dry, and not rotten. 20 Some types of citron grow with an unusual stem on one side of the fruit (in Hebrew: Pitam), and some without. For those that grow with it, this fragile stem must be kept intact; otherwise the Etrog is not ritually useable.

-

- An Etrog with its Pitam

⁋8According to an ancient rabbinic tradition attested in a text that was probably edited in Palestine around the fifth century CE, the Etrog has a very unique history. The text asks, “What was that tree whence Adam and Eve ate?” Various answers are suggested: Some rabbis think it was wheat; 21 others suggest it was a fig tree, a rather logical interpretation considering that soon after, Adam and Eve use fig leaves to cover themselves. 22 Some believe it was the fruit of the vine: again, a rather commonsensical assumption considering our knowledge about the effect of wine on the mind. Rabbi Meir explains it very clearly: “For nothing else but wine brings woe to man.” 23 By contrast, Rabbi Aba of Acre, a Palestinian sage active around the year 300 CE, is said to be certain: “It was the Etrog.” 24 The idea was repeated in later Jewish texts. Thus, for example, Nahmanides, 25 a major author of the thirteenth century, seems to follow the same identification in his commentary on Leviticus 23:40. 26

⁋9Jews were not the only ones to ask themselves what was the nature of the forbidden fruit. If the story of Eden is important in Judaism, it is tenfold still more central to Christianity. For Christians, the question was even more pressing due to the great importance they assigned to art: If one is planning to paint the scene known in Christianity as The Fall of Man or The Original Sin, one had better decide, well ahead of time, how to paint the fruit at its centre.

⁋10As is well known, in Christian artistic depictions of the mysterious fruit, the apple seems to be the most popular choice. The origin of this idea appears to be a linguistic one:

The forbidden fruit par excellence in Christian iconography is the apple, though this choice is based on a dubious linguistic connection: in Latin, malum means “apple”, “fruit” and “evil”. 27

⁋11James Snyder offers a similar, yet somewhat more complex explanation:

The identification of the forbidden fruit as an apple follows a fairly consistent pattern in the Latin West, although its etymological backgrounds are complex… Greek commentators on Genesis generally identified it with the fig tree, and it sometimes appears that way in Christian representations. Latin authorities, on the other hand, early identified the fruit of the tree as an apple. In mythology the “Apples of Hesperides,” the garden considered to be the pagan counterpart of the Earthly Paradise of Eden, provided the answer. The early Latin term Pomum, however, did not specifically refer to “apple” in the modern sense, but to various kinds of fruit produced on trees. The etymology of the “apple” as the forbidden fruit for Christian commentators was more securely traced to the Latin Malus (referred to by Vergil as an apple tree), and in the Vulgate text of the Song of Songs it was thus identified: “Under the apple tree (sub arbore malo) I raised thee up: there thy mother was corrupted, there she was deflowered that bore thee” (8:5). Since sub arbore malo was read as either “under the apple tree” or “under the evil tree” the association with Eve and the forbidden fruit was a most fitting one. 28

⁋12I do not know of early Jewish artistic renditions of the Garden of Eden in which the fruit’s nature is clear. According to the remarkable work of Alyssa Ovadis, 29 the first identification in written Jewish sources of the fruit as an apple (an identification which is not offered as a possibility in the ancient rabbinic texts we have seen) might be in the fourteenth-century polemical book Nizzahon Vetus. 30 I wonder if a saying attributed to Rabbenu Tam of the twelfth century, in which he says that an apple (Tapu’ah) mentioned in the Talmud actually refers to an Etrog, 31 is not related to the disagreement between Jews and Christians about the nature of the forbidden fruit. 32 The ancient Jewish Aramaic translation of Song of Songs 7:9—in which the words “The fragrance of your breath [is] like apples” are explained to mean “like the smell of the apples of the Garden of Eden”—might also be considered as an early hint of the idea that the forbidden fruit was an apple.

⁋13Let us go back to the identification of the forbidden fruit not with an apple, but with a citron. Was the Jewish talmudic text we have mentioned the only one to make this association? It seems the answer is no. It seems that even when some Christians spoke about some kind of “apple” when they referred to the Garden, the “apple” they had in mind was actually a citron. In fact, in some Christian medieval accounts, a fruit called “Adam’s Apple” (presumably because of the deep scratches on its skin, said to resemble the marks of teeth) 33 is mentioned. 34

-

- Citrons

-

- Lemons

⁋14The idea that the forbidden fruit was a citron actually appears in Christian art—I believe—in at least one place that I know of. In the Ghent Altarpiece, 35 known also as The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, which was created by the brothers Hubert and Jan van Eyck and completed in 1432, Eve is depicted on the top-right corner. She is holding a small fruit. 36 Although James Snyder, who wrote an entire article on this fruit, identified the fruit in the Ghent Altarpiece—correctly, I believe—with “Adam’s Apple”, 37 for some strange reason, he did not realize that this mysterious “Adam’s Apple” is almost certainly a citron 38 —this, even though he was very close to the correct identification, saying that the fruit in the picture “is small with a rough, thick skin of very bumpy texture encased by a smoother cap . . . [and] [i]t is yellow in color with shades of green and reddish-brown”, and noting for example that one of the brothers who created the piece, Jan van Eyck, “had been on important diplomatic missions to Portugal and Spain” before creating the piece. 39 Snyder remarked, regarding the Early Modern authors who suggested the fruit Eve holds in the Altarpiece is a fig: “Our early Netherlandish authors apparently had never seen a fresh fig since the fruit held by Eve is not one.” 40 One can only suggest, carefully, that Snyder apparently had never seen a citron since almost without a doubt, the fruit held by Eve is one.

-

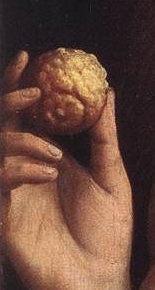

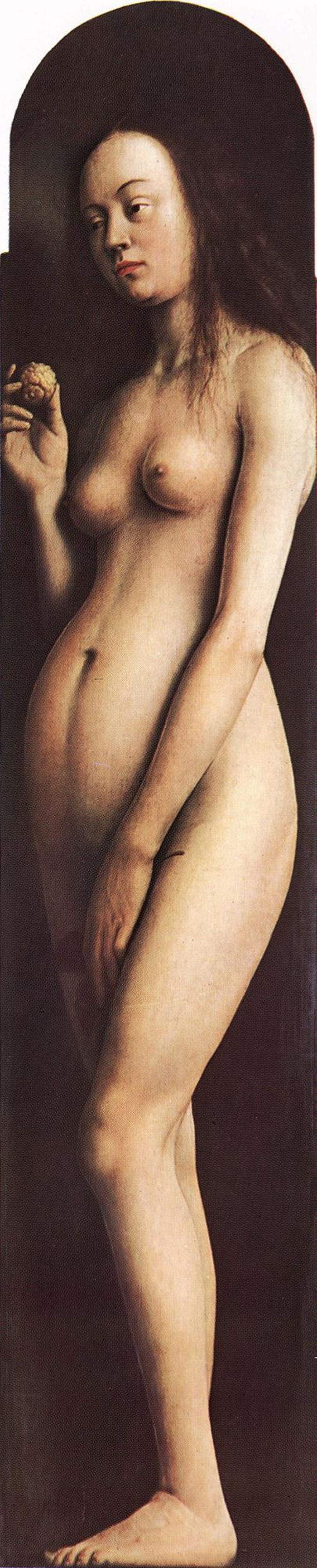

- Detail from The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, Ghent 1432

-

- Detail from The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, Ghent 1432

⁋15We have thus some proofs from both literary texts and art that the tradition stating the forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden was a citron was known also to Christians. More research is needed to find out when this tradition was first attested in Christian writings and art, though, and where. 41

⁋16Let us go back to the story of Cressus of Stamford. Our first claim is that the “Apple of Eve” that Cressus was accused of seizing was a citron, or an Etrog. Maybe it was the only Etrog the Jewish community of Stamford had, and if the theft was carried out during the festival of Sukkot (the most recent festival of Sukkot prior to the report in the Rolls took place between 2 and 9 October, 1251, three months before the case was recorded, but as explained in the introduction, after the previous visit of Henry III to the area), this could have prevented—and perhaps did prevent—the entire community from validly fulfilling the important commandment of the “Four Species”. 42 But it is also possible that this presumed theft happened after the festival and still enraged the community leaders. It is not unthinkable that the community intended to keep an Etrog from one year to the next, in case a fresh Etrog would not be available the following year. Although the fresh Etrog is the ideal fruit for the accomplishment of the religious commandment, in cases where there is lack and need, a dry one is considered, at the very least, better than nothing. 43

⁋17Based on the previous rabbinic identification of the Etrog with the fruit consumed in the Garden of Eden, it is easy to fathom that the Jewish person reporting this case to King Henri III’s agent spoke about “Eve’s Apple”, and it is even possible that the Christian person writing this report knew exactly what fruit was at stake. One can also suggest that the term used by the Jewish interlocutor made the importance of the matter clear to his Christian counterpart, as speaking about “Eve’s Apple” 44 might have rung in the ear of the official very much with a similar tone as associated with Christian relics he was certainly used to. In a society in which bones of saints, or pieces of wood from the True Cross, or the foreskin of Jesus were not unheard of, the idea that the Jews of Stamford held the Apple of Eve was probably imaginable, and maybe even rather exciting. The theft of relics was an extremely common phenomenon in the Middle Ages (and later), and authorities of various kinds tried, usually unsuccessfully, to fight against it. 45 Perhaps the king or his agent demanded a high fine, of one mark of gold, because this was also seen as an opportunity to make manifest a strong objection to such acts? I do not know, but it is a possibility worth considering.

⁋18 Why was Cressus so interested in this fruit? Many sources associate the citron with fertility and childbirth. One reason might be the rather uncommon character of the citron tree, bearing fruit all year long, with the citrons remaining on its branches for an unusually long time. It is possible, though, that other factors also played a role in the creation of this association. A Talmudic text suggests that a woman eating from the Etrog will be blessed with a child “having good smell”. 46 Another Talmudic text warns that a man who eats Etrog might have involuntary ejaculation: One can imagine that some read it as a suggestion that the Etrog enhances male virility. 47 To this day, practices involving the biting of the Etrog or its Pitam, or the eating of a jam produced from Etrogim that were previously used liturgically during the festival, are very common among traditional women who are pregnant or who would like to conceive. 48 Chava Weissler investigated a common prayer in Yiddish, which was recited by women in the Early Modern Period, in association with the biting of the Etrog. This prayer, which seems to be first attested in print in the early seventeenth century, clearly shows a certain connection that was created between the idea that the citron was the forbidden fruit, the curse of Eve in Genesis 3:16 (“I will greatly multiply your sorrow and your conception; In pain you shall bring forth children”), and a desire to overcome that curse:

Lord of the World, because Eve ate of the fruit all of us women must suffer such great pains as [almost] to die. Had I been there, I would not have had enjoyment from [the fruit]. Just so, now I have not wanted to render the Etrog unfit during the whole seven days when it was used for a commandment (mitzvah). But now, on the last day of the festival (Hoshana Rabbah) the mitzvah is no longer applicable, but I am [still] not in a hurry to eat it. And just as little enjoyment as I get from the stem of the Etrog would I have gotten from the fruit which you forbade. 49

⁋19These fertility-related traditions associated with the Etrog continue to this day. The late “rebbetzin” (a rabbi’s wife), Bat-Sheva Kanievsky, who died in October, 2011, only several weeks before the writing of this article, was the wife of a very respected rabbi, Haim Kanievsky. Among other things, she was known to collect each year, after the festival of Sukkot, Etrogim from major rabbis, and to make jam out of them. The jam was then distributed to pregnant women in the Haredi Israeli town of Bnei Brak. It was said that this jam helped those women to have an easy delivery.

⁋20I have not yet been able to find Jewish medieval sources attesting to this belief in the fertility-enhancing characters of the citron, and this is certainly a lacuna in my argument. But from the multiplicity of later sources, I do suspect some aspects of these popular beliefs have a rather long history. I do suspect that in the England of the thirteenth century, the same Jews who believed that the citron is the fruit that Adam and Eve consumed in the Garden of Eden believed also in its fertility-enhancing benefits.

⁋21Following all of these association of the citron with fertility and delivery, my second and last suggestion is that although it is not impossible that Cressus stole the Etrog because of other reasons (to accomplish the ritual himself; for financial gain; to upset other members of the community; to use it for medicinal purposes; etc.), it is also quite possible that his reason was much more personal, and even, if an historian can make an ethical judgment, rather forgivable. Ancient traditions claim, as we saw, that women who bite the Etrog or its stem after the end of the festival will become pregnant, will give birth to a male child, and will not suffer during the delivery. Perhaps Cressus and his wife (if he was married) needed some extra help with their attempts to conceive? We cannot know. But if this is true, we can only hope that the stolen “Apple of Eve” helped his wife, and that the benefits the couple perhaps gained from this act surpassed the loss from the major fine they perhaps had to pay, as well as the anger of other community members, to which they were probably subjected.

Footnotes

- 1.

- CFR 1251-2, no.173. For the image of the entry from TNA/PRO C 60/49, m.20, see http://www.finerollshenry3.org.uk/content/fimages/C60_49/m20.html, ten entries down. The entry is not in the originalia roll. The Latin reads: Mandatum est vicecomiti Suhampton’ quod inquirat per sacramentum xii. de legalioribus Judeis Winton’ super rotulum suum utrum Cressus de Stanford Judeus rapuit et asportavit a scola Judeorum eiusdem civitatis violenter pomum eve indedecus et oprobrium communitatis Judeorum Winton’ vel non. Et si per Inquisicionem illam culpabilis sit de facto illo, tunc statim distringant ipsum Cressum per redditus, domus et catalla sua ad dandum Regi unam marcam auri pro transgressione illa. Teste ut supra. per Regem. Many thanks to Lesley Boatwright for checking this transcription. Back to context...

- 2.

- CFR 1251-2, no.171. Back to context...

- 3.

- However for Henry and his queen ‘taking venison at their will’ in the forest during this stay, see G. J. Turner (ed.), Select Pleas of the Forest, (Selden Soc., 13, 1899), pp.102-103. Back to context...

- 4.

- See David Carpenter, “Crucifixion and Conversion: King Henry III and the Jews in 1255”, the Fines of the Month for January and February 2010. Back to context...

- 5.

- Close Rolls 1247-51, 553: ‘Monstravit regi Samar’ de Winton, Judeus, quod justiciarii ad custodiam Judeorum assignati ipsum gravant indebite...’ Back to context...

- 6.

- For Henry III’s gold treasure, see David Carpenter, “The Gold Treasure of King Henry III”, chapter 6 of his The Reign of Henry III, Continuum, London 1996. Back to context...

- 7.

- Stamford in Lincolnshire is located about 90 miles north of London. The Jewish community there was attacked at least twice, in 1190 and in 1222. Nevertheless, proofs exist that some relatively peaceful phases existed as well. See Cecil Roth, “Stamford”, in Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik (eds.), Encyclopaedia Judaica 2nd Edition (EJ2), (Macmillan Reference USA, Detroit 2007), vol. 19, p. 158. Back to context...

- 8.

- See Bracha Yaniv, “Torah Ornaments”, in: EJ2, vol. 20, pp. 50-53. Back to context...

- 9.

- All biblical translations follow the New King James Version (NKJV) of 1975. Back to context...

- 10.

- Plural: Etrogim. The origin of the term Etrog seems to come from the Persian word narang, and the Sanskrit word narangas. On relics of names for the Etrog that are even closer to these original terms, see Babylonian Talmud (hereafter BT) Kiddushin 70a. The name “orange”, assigned to another member of the citrus family, probably has the same origin. For a basic discussion on the identification of the other species, see Walter Jacob, “The Mysterious ‘Lulav’ and ‘Etrog’: A Preliminary Study of Jewish Symbols”, in: Walter Jacob (ed.), Gardening from the Bible to North America: Essays in Honor of Irene Jacob (Rodef Shalom Press, Pittsburgh 2003), pp. 13-40. Back to context...

- 11.

- A fascinating text in Nehemiah 8:14-18 describes a celebration of the Sukkot festival in the fifth century BCE. According to this text, is possible that olive was identified as one of the species. Back to context...

- 12.

- The reluctance to simply say “it appears”, without the qualifying “seems”, is due to the possibility that the object described on these coins is not actually a citron, but a pine cone, as suggested by some. On the frequent use of the Etrog (together with the branch of the palm tree, the Lulav) on Jewish coins and seals in later periods, too, see Arie Kindler, “Lulav and Ethrog as Symbols of Jewish Identity”, in Robert Deutsch (ed.), Shlomo: Studies in Epigraphy, Iconography, History and Archaeology in Honor of Shlomo Moussaieff (Archaeological Center Publication, Jaffa 2003), pp. 139-145. See also Rivka Ben-Sasson, “The Etrog in the Palestinian Mosaics—is it only a Jewish symbol?” (Hebrew), in Online Proceedings of the Fifteenth World Congress of Jewish Studies (August 2-6, 2009). [http://jewish-studies.org/imgs/uploads/proceedings/etrog.pdf]. Back to context...

- 13.

- As one can see, the opinions on many of the matters described here are rather diverse, and although recent generic studies seem to provide concrete answers to some of the questions, others are still debatable. Two books by Samuel Tolkowsky on citrus fruits in general, both beautifully edited and containing a great number of images of various kinds, one published in English (Hesperides: A History of the Culture and Use of Citrus Fruits, J. Bale, Sons and Curnow, London 1938), and one, extended and revised, in Hebrew (Citrus Fruits: Their Origin and History throughout the World, The Bialik Institute, Jerusalem 1966), are still goldmines and a good starting point on the matter. For a good summary of the various opinions regarding the appearance of the citron in Palestine, and refuting an early date by highlighting the absence of citron seeds, or pieces of its wood, in archaeological excavations, see Gideon Biger and Nili Liphschitz, “The Etrog – Is it ‘Pri Etz ha-Dar’? On the Question of the Existence of the Etrog in Israel in the Past” (Hebrew), Beit Mikra 148 (1996), pp. 28-33. On related issues, see Erich Isaac, “Influence of Religion on the Spread of Citrus”, Science, New Series 129 (1959), pp. 179-186. [http://www.jstor.org/stable/1755393]; Alfred C. Andrews, “Acclimatization of Citrus Fruits in the Mediterranean Region”, Agricultural History 35:1 (1961), pp. 35-46 [http://www.jstor.org/stable/3740992.]; R. Carvalho, W. S. Soares Filho, A.C. Brasileiro-Vidal, M. Guerra, “The Relationships Among Lemons, Limes and Citron: A Chromosomal Comparison”, Cytogenetic and Genome Research 109:1-3 (2005), pp. 276-282; Elisabetta Nicolosi, Stefano La Malfa, Mohamed El-Otmani, Moshe Negbi and Eliezer E. Goldschmidt, “The Search for the Authentic Citron (Citrus medica L.): Historic and Genetic Analysis”, HortScience 40:7 (2005), pp. 1963-1968. [http://hortsci.ashspublications.org/content/40/7/1963.full.pdf+html]. For a very recent discovery of evidence for the cultivation of citrons near Jerusalem as early as the fifth or fourth centuries BCE, see www.haaretz.com/print-edition/news/jerusalem-dig-uncovers-earliest-evidence-of-local-cultivation-of-etrogs-1.410505. I would like to thank Oded Lipschits, one of the archaeologists who studied the site, and my colleague Jodi Magness, for helping me to obtain detailed information about this fascinating discovery. Back to context...

- 14.

- See also Erich and Rael Isaac, “The Goodly Tree”, in Philip Goodman (ed.), The Sukkot and Simhat Torah Anthology (Jewish Publication Society, Philadelphia 1998), pp. 156-167. Back to context...

- 15.

- On the interesting story of a Presbyterian farmer who is the only large-scale grower of Etrogim in the US, see Miriam Krule, “Etrog Man”, Tablet Magazine, October 12, 2011. [http://www.tabletmag.com/ life-and-religion/80571/etrog-man/]. Back to context...

- 16.

- Sicily was possibly one of the sources for citrons, but also Italy (particularly, the area of Calabria), Spain, and Corfu. On the movement of Etrogim between communities, see the thirteenth-century Or Zaru’a II, Shabbat 84, and the fifteenth-century Lekket Yosher I, 149b. Back to context...

- 17.

- At the same time, Nicolosi et al., p. 1968, suggest that Jewish planters had major impact on the wide geographical distribution of citrons. For a fascinating report on the European commerce of citrons for Jews at the end of the nineteenth century, and especially on the way this commerce was carried out in the major port of Trieste, see “The Citron in Commerce (Citrus Medica, Risso.)”, Bulletin of Miscellaneous Information (Royal Gardens, Kew) 90 (1894), pp. 177-182. [http://www.jstor.org/stable/4119524]. It seems merchants, who had difficulties in pronouncing the word Etrog, called this peculiar fruit Troon. Back to context...

- 18.

- For a testimony reporting that in twelfth-thirteen century Northern France Etrogim often arrived still green, and changed to yellow only later, see Tossafot, Sukkah 31b. For a report explaining that the cost of a valid Etrog is high, at least more than the cost of three meals, see Tossafot, Sukkah 39a. Back to context...

- 19.

- In 2011, the price range for an Etrog worldwide (excluding delivery) was generally the equivalent of between five to fifty British Pounds, though one could have easily found Etrogim with higher price tags. Back to context...

- 20.

- See, for example, Mishnah Sukkah 3:5-7. Back to context...

- 21.

- For an explanation of how the text could be understood to refer also to things we would not call “fruits” today, see Alyssa Ovadis, “Abstraction and Concretization of the Fruit of The Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil As Seen Through Biblical Interpretation and Art” (Master’s Thesis, The Department of Jewish Studies, McGill University, Montreal 2010), pp. 41-42 and 46-47. Back to context...

- 22.

- For a similar interpretation see also BT Sanhedrin 70b. Back to context...

- 23.

- BT Sanhedrin 70ab. A similar idea appears also in the Greek Apocalypse of Baruch (III Baruch), 4:8-13. Back to context...

- 24.

- Midrash Bereshit Rabbah, Vilna ed., 15:7. See an interesting literary and philosophical analysis of this rabbinic text in Yisrael Rosenson, “What Tree Was That? On Midrash, Exegesis, and Educational Thought” (Hebrew), Hagut: Jewish Educational Thought 3-4 (2002), pp. 51-74. Rosenson suggests (p. 56), rather convincingly, that the mention of the Etrog did not exist in the earliest strata of this text. Back to context...

- 25.

- Moshe ben Nahman, 1194–1270. Back to context...

- 26.

- For a rather bizarre article that attempts to identify the forbidden fruit with the Etrog, considering—it seems—the Biblical story as historical, and proving the point by—among other things—examining the arrangement of the leaves (phyllotaxis) of this tree, see Mordechai Kislev, “‘The Tree of Knowledge was Etrog’” (Hebrew), Sinai 125:1-2 (2000), pp. 9-18. Back to context...

- 27.

- Rosa Giorgi, Angels and Demons in Art, edited by Stefano Zuffi and translated by Rosanna M. Giammanco Frongia (J. Paul Getty Trust Publications, Los Angeles 2003), p. 103. Back to context...

- 28.

- James Snyder, “Jan Van Eyck and Adam’s Apple”, in: The Art Bulletin 58:4 (1976), pp. 511-515. [http://www.jstor.org/stable/3049564]. Back to context...

- 29.

- See above, note 21. Back to context...

- 30.

- David Berger, The Jewish-Christian Debate in the High Middle Ages: A Critical Edition of the Nizzahon Vetus (Jason Aronson, Northvale, 1996), p. 218. See Ovadis, pp. 49-50. Back to context...

- 31.

- See Raabenu Tam’s quote (1100–1171) in Tossafot, incipit “pri”, BT Shabbat 88a. Back to context...

- 32.

- For another suggestion regarding this saying of Rabbenu Tam’s, see Hayim Talbi, “The Custom of Eating an ethrog on Rosh Hashanah” (Hebrew), Morashtenu Studies 2-3 (2004), pp. 119-135. Back to context...

- 33.

- See an eighteenth-century summary in the entry “Adams-apffel”, in Johan Heinrich Zedlers, Johan Heinrich Zedlers Grosses vollstaendiges Universallexicon aller Wissenschafften und Kuenste, Halle and Leipzig 1732, Vol. I, pp. 265-266. Back to context...

- 34.

- Assaf Gur, in his The History of the Etrog (Pri Etz Hadar) in the Land of Israel in All Periods (Hebrew), (Agricultural Publication Division, Tel Aviv 1966), p. 29, mentions several medieval travellers from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, including Geoffrey of Vinsauf, Tietmar, and Jacques de Vitry, who reportedly said the citron is called “Adam’s Apple”. I was not able to find the sources and verify these claims. Back to context...

- 35.

- See http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8c/Lamgods_open.jpg. Back to context...

- 36.

- For a high-resolution image of Eve, see http://www.shafe.co.uk/crystal/images/lshafe/van_Eyck_The_Ghent_Altarpiece_Eve_1425-29.jpg One of the major studies on this piece is Lotte Brand Philip, The Ghent Altarpiece and the Art of Jan van Eyck (Princeton University Press, Princeton 1971). Back to context...

- 37.

- See Snyder, p. 513. Back to context...

- 38.

- Ovadis, perhaps because of an admiration for scholarly work and a fear of contesting important scholars’ conclusions—a rather understandable stance in a master’s thesis—accepted Snyder’s conclusion on the matter. See Ovadis, pp. 56-57. Back to context...

- 39.

- Snyder, pp. 512-513. Back to context...

- 40.

- Snyder, p. 513. Back to context...

- 41.

- Rivka Ben-Sasson (http://jewish-studies.org/imgs/uploads/proceedings/etrog.pdf, p. 12) also suggests that in a mosaic from the fifth century Church of the Priest John (I believe she refers to the one in Khirbat al-Mukhayyat, in current-day Jordan), there are fruits that seem to be citrons within a description that she believes to be of Paradise. Although tempting, based on observing the pictures available online, I am not certain regarding this assessment of the mosaic. See http://198.62.75.1/www1/ofm/fai/FAImukh2.html. Back to context...

- 42.

- The act of causing one's Etrog to be lost (by damaging it, losing it, or perhaps stealing it) was probably not an unheard-of act in Jewish communities. I am aware of two reports in the Jewish legal responsa literature of such happenings. It should be noticed that in both cases it is not clear if the act was actual theft or something else that made the Etrog non-valid or lost. See a case discussed by Moses ben Isaac Mintz (Mainz, c.1425 - Posen, c.1480) in his Shut Maharm Mintz, 113, and another by Tzvi Ashkenazi (Moravia c.1660 - Lemberg 1718), in his Tshuvot Hakham Tzvi 120. Back to context...

- 43.

- On the custom of eating the Etrog on the day after the holiday of Sukkot, see Roke’ah, Sukkot 222. From other texts, it is clear that at times, some Etrogim were left to dry. The Etrog dries generally rather nicely, and a dry Etrog can be kept for years. On the possibility of using an invalid Etrog—for example, a dry one—in case a valid one is not available, at least during some days of the festival, see Tossafot, Sukkah 31a; Meiri, Bet ha-Behirah Sukkah 31a; Rabbenu Asher, Sukkah 3:14; Mahzor Vitry 364; Siddur Rashi 300; Ha-Manhig Sukkah 381; Or Zarua II, Sukkah 306. Back to context...

- 44.

- About calling the Etrog an apple (Tapu’ah), see the following twelfth-/thirteenth-century texts: Tossafot, Shabbat 88a; Rabbenu Tam’s Sefer ha-Yashar (Novellae), 263. Back to context...

- 45.

- See Patrick Geary, Furta Sacra: Thefts of Relics in the Central Middle Ages (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1978); Patrick Geary, "Sacred Communities: The Circulation of Medieval Relics", in Arjun Appadurai ed. The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective (Cambridge University Press, New York 1986), pp.169-191. Back to context...

- 46.

- BT Ketubbot 61a. Back to context...

- 47.

- BT Yoma 18a. Back to context...

- 48.

- See various references, some from the Early Modern period, to such customs as practiced in various Jewish communities, in Yom-Tov Levinsky, “Etrog’s Stem and a Baby’s Foreskin” (Hebrew), Yeda Am 1:5-6 (1949), pp. 2-3. See also Assaf Gur, The History of the Etrog (Pri Etz Hadar) in Eretz Israel in All Periods (Hebrew) (Agricultural Publication Division, Tel Aviv 1966), p. 25; Herman Pollack, Jewish Folkways in Germanic Lands (1648-1806): Studies in Aspects of Daily Life (The M.I.T Press, Cambridge, 1971), p. 17. Back to context...

- 49.

- Translation from Chava Weissler, “Prayers in Yiddish and the Religious World of Ashkenazic Women”, in Judith R. Baskin, Jewish Women in Historical Perspective (Second Edition, Wayne State University Press, Detroit 1998), pp. 176-177. See also Chava Weissler, “Mizvot Built into the Body: Thkines for Niddah, Pregnancy, and Childbirth”, in Howard-Eilberg-Schwartz (ed.), People of the Body, Jews and Judaism from an Embodied Perspective (New York, 1992), pp.101-115; Chava Weissler, Voices of the Matriarchs (Beacon Press, Boston, 1998). For a rather similar custom attested to by a rabbi from Turkey, see Haim Palachi (1788-1869), Mo’ed le-Khol Hai, Izmir 1862, p. 208b, a. 25. Back to context...